The Game That Ate Itself

How AI makes “winning” taste like demand collapse

Anthropic recently revealed that almost all of the code enhancing Claude is now written by Claude itself, under human guidance. This self-bootstrapping isn’t unique to Anthropic. Every major AI lab is racing toward the same threshold: systems that outperform even Nobel-caliber humans across every cognitive task.

Most think tank and academic work on AI displacement rests on two backward-looking claims: technology usually automates tasks rather than whole jobs, and new labor-intensive sectors always emerge to absorb the displaced. Both made sense when manufacturing and services rose alongside automation, when capital and labor were geographically coupled, and when winner-take-all dynamics were weaker.

Those guardrails no longer hold. Generative AI plus instant global distribution means cognitive automation can scale across millions of roles simultaneously, without creating new mass-employment industries to offset the losses.

This essay models what happens when AI doesn’t just augment but substitutes, gradually catching and then surpassing human cognitive labor across the economy. We can understand the logic through a simple game between firms, where locally rational choices add up to macroeconomic self-destruction. Call it The Game That Ate Itself.

Rules of the game

We can understand how AI‑driven automation plays out by treating it as a simple game between firms.

The game has two competing firms that split a market between them. Both are rational, strategic decision‑makers trying to maximize long‑run profits. Crucially, total demand for their products depends on aggregate consumer income.

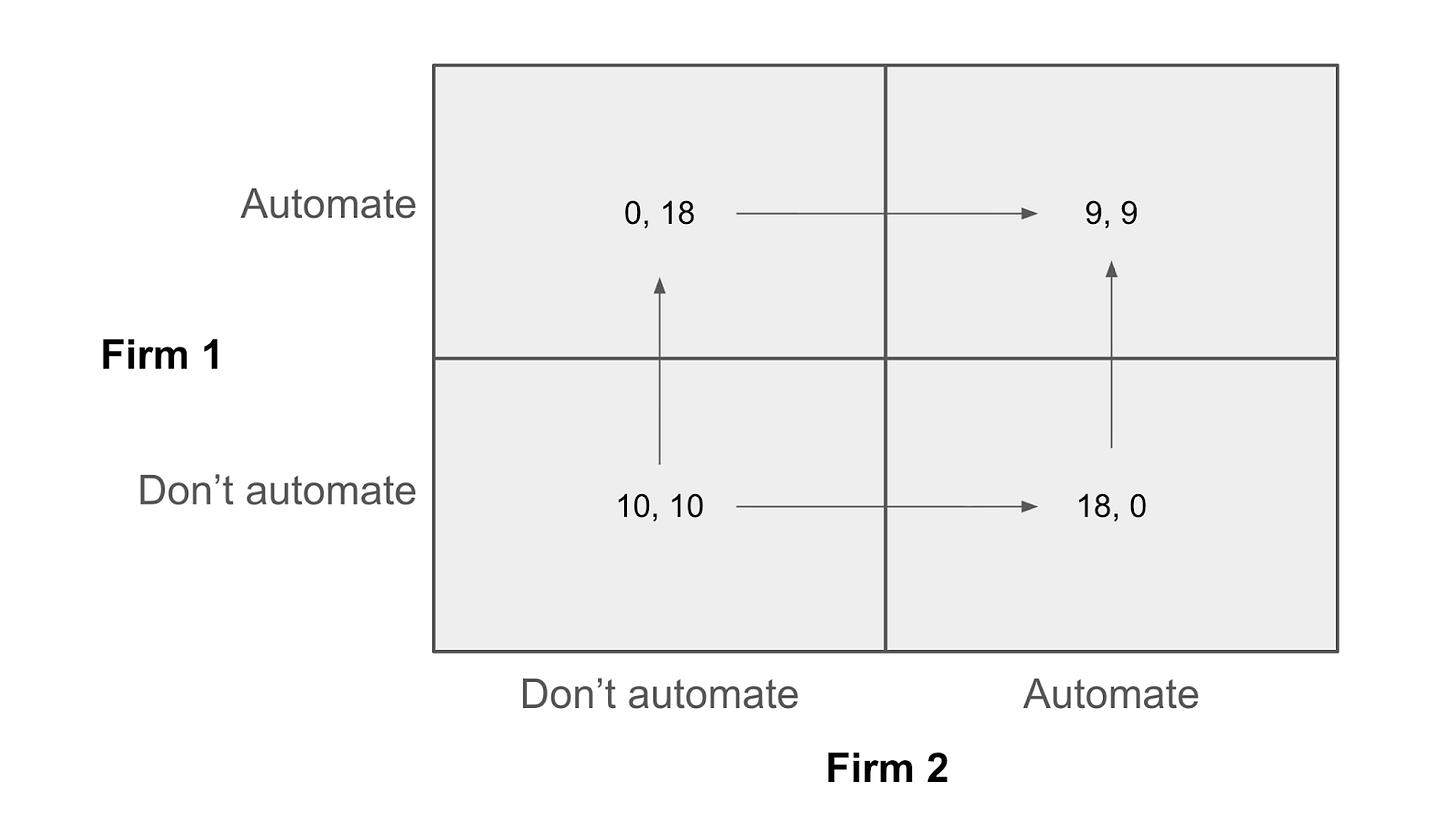

Each cell in the payoff matrix represents the net present value of the firm’s future profits; a payoff of zero means the firm has effectively exited the market.

Each quarter, every firm chooses between two actions: keep operating under the current cost structure, or invest in and deploy more automation. At any point in time, their choices produce a payoff matrix like this:

Both firms start in the “don’t automate” cell. From there the four outcomes line up like a classic prisoner’s dilemma:

Reward (R): If neither automates, they enjoy stable demand and profits.

Temptation (T): If I automate and you don’t, my costs drop, I undercut you, and I take the market.

Sucker (S): If you automate and I don’t, I get wiped out.

Punishment (P): If we both automate, neither gains advantage; we just reset the game with lower costs and no extra share.

This isn’t a one‑shot decision; it repeats every quarter. Each period, both firms decide whether to introduce more automation. In a textbook iterated prisoner’s dilemma, the canonical “good” strategy is tit‑for‑tat: start by cooperating, match your rival’s last move, and punish defection but forgive quickly. On paper, that ought to stabilize the market. Here, it doesn’t.

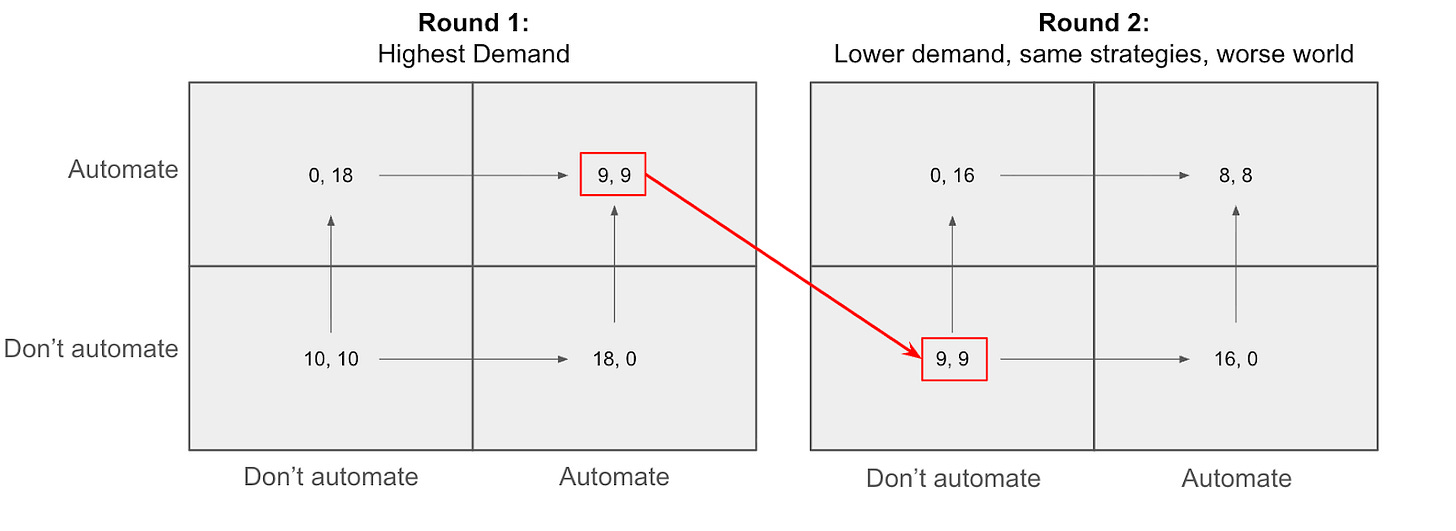

The usual stabilizing mechanism completely breaks down here because playing the game eats the board. Every round of automation reduces the amount of labor needed for the same output. Lower labor income erodes demand, reducing the size of the market in all future rounds.

In formal terms, the per‑round payoff matrix is a function of a hidden state variable, aggregate demand, that declines whenever firms defect by automating. The more rationally they play, the faster they saw off the branch they’re sitting on.

Now scale from two firms to thousands across the whole economy. The right move for any given firm in any given quarter is to automate a bit more. Even if every executive fully understands that these locally rational choices add up to macroeconomic destruction, none of them has a credible way to coordinate restraint. The iterated nature of the game is what makes it a trap rather than an obviously suicidal choice: each round only erodes a little demand, but refusing to play in any round is indistinguishable from choosing to die.

Under these rules, the Nash equilibrium is not a stable prosperity but a slow‑motion economic catastrophe. Most firms and households are either wiped out or pushed to the margins. Given these dynamics, what would it take to change the outcome?

Remaking the game

The payoff structure of the automation game leads straight toward economic self‑destruction. Once we accept that the Nash equilibrium is bad, the only real question is how to change the game. All serious proposals fall into some mix of coordination or rule‑changing. What follows is a survey of those levers and whether they actually touch the mechanism.

Taxing and redistributing the automation dividend shifts some surplus from AI‑intensive firms (or capital returns) into income floors or wage subsidies. In principle, this keeps demand alive even as direct employment shrinks.

The obvious obstacle is jurisdictional arbitrage: capital moves faster than tax regimes. Any serious version would need OECD‑style minimum coordination, but faster, broader, and with actual teeth rather than polite statements.

Shorter standard workweeks try to share the remaining human‑necessary work across more people by cutting hours (for example, a four‑day week). Proponents argue this preserves employment, dignity, and broad consumption while still cashing in productivity gains. Making that stick requires strict labor law, which re‑opens the jurisdictional arbitrage problem: work flows to regions with weaker protections. Countries can end up racing to the bottom on labor standards the way Ireland raced to the bottom on taxes.

The deeper problem is that it assumes there is still meaningful human work to distribute. If AI is genuinely substitutive across most cognitive tasks, the policy shifts from sharing real work to inventing make‑work to preserve the employment‑to‑consumption loop. It may have value as a transitional measure, but it papers over a structural break rather than addressing it.

Job‑transition guarantees scale something like Trade‑Adjustment Assistance into the automation era: if your role is automated, you get guaranteed income and funded retraining into sectors where humans remain bottlenecks. Conceptually, it mirrors shorter workweeks; both only work if there is still enough non‑automatable work somewhere in the economy.

Variants like Just Transition Framework try to push the cost of retraining onto the firms that cause the displacement. That sounds fair until you remember the competitive landscape: any burden that falls only on incumbents and not on AI‑native firms just accelerates the incumbents’ collapse. AI‑native firms have no legacy workforce to retrain, so the rule turns into a competitive moat for exactly the firms driving the disruption.

Stronger labor regimes try to give workers more say in how AI is deployed internally, pushing toward augmentation rather than outright replacement. In the extreme, this collapses into a neo‑Luddite technology ban. Instead of changing the payoff structure, it effectively cancels the game by making automation itself off‑limits.

As with job‑transition guarantees, it is almost impossible to design this without disproportionately punishing incumbents. The more fundamental problem is that the game is multi‑level: the domestic labor market sits inside the game of remaining a sovereign nation. If you take seriously arguments that whoever controls AI controls everyone else, unilateral restraint starts to look less like virtue and more like a suicide pact with your own citizens.

Completing the circuit

Taken seriously, all of the labor‑law‑first options fail on their own terms. That leaves redistribution not as an ideological preference but as the only lever that actually touches the mechanism.

Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty‑First Century argues that when the return on capital exceeds the growth rate of the economy (the famous r > g), wealth concentrates. The larger the gap between r and g, the faster that concentration happens. Piketty is describing a world of factories and land.

When capital returns come from owning the substitute for human cognition itself, that divergence accelerates catastrophically. The asset that is appreciating (AI capital) is the same asset that is destroying the underlying source of labor income. Returns to capital not only outpace growth; they actively crush the labor share that used to anchor demand.

The standard redistribution debate is so fraught because it centers on deservedness: do people have a right to income they didn’t “earn”? That framing invites endless moral combat and lets opponents anchor on welfare dependency and the dignity of work. In the context of mass automation, redistribution is not about whether displaced workers deserve to eat; it is about whether the firms that displaced them still want customers. Ethics give way to plumbing.

The companies building the most powerful automation in history are, directly or indirectly, entirely dependent on the consumer economy that automation is eroding. If we follow the logic to its endpoint: a few AI companies automate everything, capture all of the surplus, and then… sell to whom? Each other? We end up with a handful of firms sitting on infinitely productive capital but have no one to monetize it against. If you’re looking for a reason to be hopeful, this is it. The companies that most need someone to pull the redistribution lever are the ones building the trap.