The Average Customer and Other Hallucinations

At a DTC brand I worked with, the average new customer placed 2.5 orders in their first year. This statistic came up constantly — board decks, roadmaps, acquisition modeling — because it seemed to reveal something essential about “the typical customer.” It wasn’t treated as a mathematical artifact; it was treated as identity. It shaped marketing spend, retention strategy, and even product features.

Another well-known fact was that more than half of new customers churned after their first order. The breakthrough came only when we combined these two truths. If over half of customers placed exactly one order, yet the average was 2.5, then the remaining customers must place far more than 2.5 orders to pull the mean upward.

When we removed the one-and-dones, the picture snapped into focus: the customers who stayed placed over six orders in their first year.

The distribution wasn’t centered at all; it was bimodal. And the “average buyer” the company had been building around for years did not exist; it was a mathematical hallucination. That hallucination drove the wrong LTV model, the wrong acquisition strategy, the wrong retention messaging, the wrong product priorities, and, most dangerously, the wrong mental picture of who the customer even was.

There were many possible contributors to this fractured pattern: targeting failure, onboarding failure, experience failure, positioning failure, expectation failure. The most important insight was not which one was at fault — it was that the average concealed the very structure of the system.

Once we de-averaged the data, the “typical customer” vanished, and a missing segment emerged. The business stopped optimizing for a fictional 2.5-order persona and started asking a question that transformed the business: Why can’t we retain a customer who should naturally buy two or three times a year?

Seeing Like a Company

The problem we just described isn’t a data science problem, a product maturity problem, or even a business problem; it’s a recurring structural error in how humans manage complexity at scale. Smart people have been making this mistake for over 200 years across every imaginable institution, starting with the first modern states. The pervasiveness of this problem hints that the cause is not stupidity; it’s necessity.

We continue to use averages because they solve the problem of legibility. James C. Scott describes this challenge in Seeing Like a State. Reality is messy and complex. The only way it can be understood, recorded, and controlled from a central location is by standardizing and simplifying this reality. Innovations imposed from above like standardized surnames, cadastral maps, censuses, and fixed property boundaries made societies legible to their governments, enabling the first modern states to emerge. Scott shows us:

Compression is unavoidable. Legibility is the price of operating at scale.

Information loss is not neutral. What you erase shapes what you can see.

Some losses are fatal. Flatten the wrong structure and you lose the ability to act.

Legibility has produced policy failures and even disasters. When Tanzania forcibly relocated millions into planned villages, officials optimized for what they could see from the capital: neat grids and standardized plots. In the process, they destroyed the local knowledge that had made the land productive. The history of central planning is littered with five-year plans optimized for legible abstractions that bore no resemblance to ground truth. The pattern is always the same: the map becomes more real than the territory, and the territory suffers. Legibility is a tool, and this tool can become a worldview. The abstraction is mistaken for reality, making it impossible to understand and act upon the system.

Modern corporations face similar challenges. It is impossible for a company to understand its business, plan, and execute using the messy reality of individual customers, orders, and items sold. We often turn a jagged, heterogeneous, multi-modal distribution of human behavior into single numbers: the average order count, the average user, the average session, the average funnel.

The metric becomes an object of reasoning. Once that happens, strategies are built around the abstraction, incentives are optimized around the abstraction, and evidence that does not fit the pattern is dismissed as noise. Averages are dangerous not because they are wrong, but because they are so easy to reason with.

Legibility is required to operate at scale. The simplifications that produce legibility must preserve relevant pieces of the structure of the underlying reality to enable understanding and effective control. Averages erase that structure.

Heterogeneity in Practice

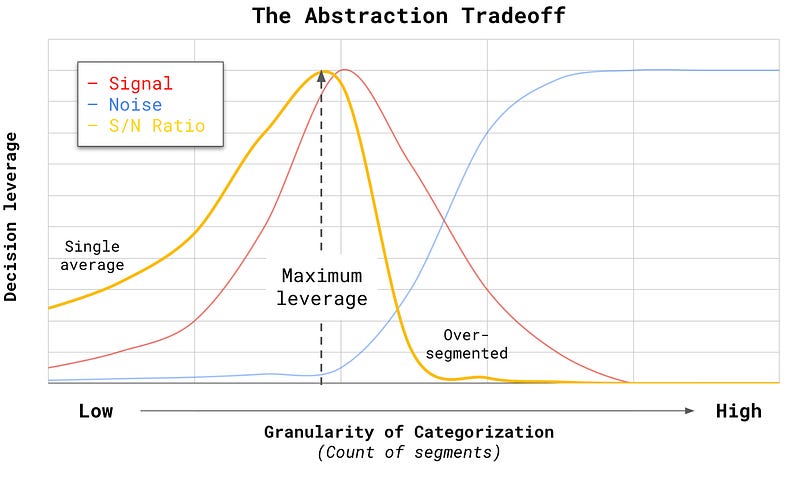

Averages are an extreme. They homogenize populations, eliminating noise, but losing signal in the process. If we view the other extreme, pure heterogeneity, the picture is even worse. If every customer or order is treated as fully unique, there are no patterns, no learning, no generalization, no leverage, and therefore no scalability. The solution lies in viewing heterogeneity as a discipline rather than a principle.

The skill is discerning which distinctions matter and which can be safely discarded, with the goal of having the fewest categories that let us understand and control the system in question. A categorization is justified only if it increases our ability to explain, predict, or intervene in the system. All segmentation is descriptive, but it is only worth the cognitive cost if it is actionable.

We can approach a new system through the lens of information gain — how much our understanding and ability to act improves with the next incremental feature. We can consider a list of the many ways we can segment customer and order data while keeping this test in mind: Does knowing that someone belongs to this segment change what I would do? Adding segments in order of maximum information gain until we reach diminishing returns provides the minimum abstraction that preserves the structure necessary for understanding and control.

How to read the chart:

At the left extreme, everything is collapsed into a single average.

Noise is minimal, but most decision-useful signal has been lost: we can observe change, but not identify what is driving it or how to intervene.As categorization becomes more granular, signal increases rapidly while noise grows slowly.

Breaking the average reveals structure in the system, enabling explanation, prediction, and targeted action.Beyond a point, additional granularity fragments the system.

Sample sizes shrink, interactions explode, and noise grows faster than signal, reducing, rather than improving our ability to reason and act.

There are a few archetypal mistakes that violate the information-gain rule. Convenience segmentation optimizes for ease of creation rather than usefulness. These segments are often inherited from infrastructure (channel, acquisition source, product category) or inherited from vendors (mirroring what the provider sold you), or inherited from history (decisions someone made years ago that nobody revisited).

This last failure mode is especially common because the right abstraction is only right at a moment in time. Young companies with low volumes need coarse groupings to learn anything. As companies scale, finer distinctions become meaningful. As product lines & customer bases evolve, new groupings become necessary to understand, predict, and drive performance.

Vanity segments are those that feel sophisticated but don’t differentiate behavior. “Millennials” or “premium customers” may sound strategic while lacking the predictive power to change decisions. Performative segments exist to satisfy a stakeholder or a decision already made. The “need to understand our Gen Z customer” may follow a decision to launch a TikTok campaign, not the other way around.

It’s critical to get segmentation right because segmentation’s costs aren’t just analytical, they’re organizational. More categories means more metrics, more metrics beget more owners, more owners require more coordination, and more coordination slows decision making. Heterogeneity can reveal structure, but cannot tell you what to value nor how to make these tradeoffs.

Thus, we arrive at a set of organizational problems. First and foremost, who holds the model? Who holds the line when proposed segments do not aid decisionmaking? Who revisits structure periodically and questions if the segmentation developed two years ago is still highly effective today? What roles do people at different levels in the organization, from individual contributors to executives, play in building and maintaining this structure?

The Compression Bargain

Different levels within organizations face vastly different information environments. This necessitates a division of sensemaking responsibilities.

Front-line operators, PMs, analysts, and domain experts live in distributions. They see the tails, the modes, and the instabilities. They understand why the average moved, and surface causal structure, not just metrics. People at this level can afford to zoom in to see more detail with a narrower field of view. This is the only way they can interpret what they are seeing and make informed decisions about what to do next.

Senior leaders live in a world of averages out of necessity. Leaders constantly wrestle with the challenge of information overload. For them, averages are a critical form of compression that they rely on to understand the business. If leaders tried to live in raw distributions, they would fail at their job. An average, however, tells you nothing about what is moving the average.

Middle managers translate between these two realities, giving them the most challenging job in the organization. They take inputs from the front-line teams and decide what information to compress, what to preserve, and what to leave out in their communications with senior leadership. Middle managers are incentivized to make information legible to senior leaders, giving them a structural bias towards overflattening.

Trust is the bridge between these realities that allows the system to flex when it needs to. Epistemic trust — trust that someone will interrupt the compression layer only when it matters, and that doing so will not be punished.

It is incumbent on middle management to understand the information environment senior leaders face. This means surfacing compressed, even highly compressed information most of the time, while developing exceptional judgment around when compression is likely to lead to poor resource allocation decisions at the senior leadership level. It also requires skilled communication to explain why additional detail is warranted at this time, for this topic, otherwise the detail is perceived as academic or overcomplicated.

Senior leadership’s half of this contract is allowing middle managers to build trust and credibility specific to information sharing. Trusting someone to surface important exceptions requires actually engaging when they do. If a middle manager raises “the average is hiding something” and gets dismissed or deprioritized, they will quickly learn not to raise it again. The senior leader’s job isn’t just to grant trust; it’s to honor the bet when someone spends their credibility. This means treating the interruption as signal, not noise, even when it’s inconvenient. When this contract breaks, organizations don’t just make bad decisions; they stop learning.

Building a Trust Economy

Creating an environment with the trust necessary to surface the right information at the right time takes intentional effort because the incentives are asymmetric. Raising an exception is costly. It burns credibility, risks being seen as academic, and slows decisions. It can look like poor judgment in hindsight. Ignoring exceptions is cheap. Nothing breaks immediately, accountability is diffused, and failure is frequently delayed and deniable. The truth fails to surface not because it is unknown, but because surfacing it is irrational under default conditions.

Middle management must learn how to spend credibility well, and this comes through rare, disciplined escalation. In practice, this looks like bringing both the compressed signal and, when appropriate, the minimum required additional depth for understanding. These exceptions should be framed as decision-relevant rather than intellectually interesting, and explicit about why the average is unsafe this time. The meta-signal is that you understand senior leadership’s need for compression, and you’re interrupting it intentionally.

Senior leadership must understand how trust is earned and destroyed. Trust is built by what happens after someone takes a risk. In practice, this means delaying judgment and asking clarifying questions instead of deflecting when someone surfaces a greater level of detail. Leaders can reinforce the behavior by closing the loop later (e.g. “You were right to flag that”) and not punishing false positives when the reasoning was sound. Inconsistency kills trust. If sometimes exceptions are welcomed, and sometimes dismissed, without a clear pattern, middle managers can’t learn when it’s safe to speak.

This trust must be built in advance of moments of crisis when averages are inappropriate because you can only spend the trust you have already accumulated. In practice, this means that leadership must show curiosity before the stakes are high, and middle managers must demonstrate good management before escalation matters. Smaller, low risk interruptions are practice reps for when it matters.

These reps can come through rituals and norms. A few practices worth considering:

Unpack an average in regular meetings. Make this part of a quarterly or monthly business review. The average should be unpacked with the intent of understanding how the component parts drove decisions this period. This framing makes the exercise useful rather than academic. This builds not only the muscle of looking, but also a shared understanding of the power of this practice. Leaders come to expect to see distributions and learn to ask what’s underneath when an average moves. The practice serves both sides.

Extend postmortems to epistemic failures. Blameless postmortems are already utilized in many organizations and are well-suited here. Postmortems frequently focus on execution failures. Here, we extend them to epistemic failures — when we had the data but compressed it too far, or chose a metric that hid the problem. Keeping postmortems blameless, by asking what we missed rather than who missed it, keeps the focus on calibration rather than accountability.

Name when you’re spending credibility. This is the most cultural and hardest to formalize. Shared language (e.g. “I’m spending credibility here”) lets everyone know they’re raising something outside of the usual flow. This differentiates routine updates from genuine exceptions and tells senior leaders that this is the moment to engage. This works only if it’s rare and honored when used.

The key to all of these practices is that they are embedded in existing structures, so they don’t require additional calendar space or new political capital to establish. Adapt these to your organization with this principle in mind.

The hard part isn’t knowing what to do; it’s making it safe to do it. Organizations don’t fail when averages lie; they fail when no one is authorized to say so.